Have you heard that submarine cable fiber pairs will eventually become a standard unit of purchase? I have. And it prompted me to roll up my sleeves and do some fact-checking.

Are people going to be buying fiber pairs? Will carriers? Enterprises?

We have a few ways to test the claim that fiber pairs will become the new coin of the realm.

First, we can examine the primary unit for measuring supply and demand. Is counting up fiber pairs that are sold and free for supply a useful metric for understanding volume?

Second, we have price. Are people actually going to buy those fiber pairs? If so, what would it cost?

Let’s get into it.

Measuring Scarcity

I started by using fiber pairs as a way to measure scarcity. We typically measure how much capacity we have on a route in bits. You add up how many potential bits there are across all available cables (if they were lit), compare to how much is actually lit, and measure the gap as the overhang.

Last time we looked at the Atlantic, there was a huge overhang. Only about 30% of potential bits were lit. That would lead us to believe that we have a huge amount of supply, right?

Not so fast. Let’s count the number of free fiber pairs.

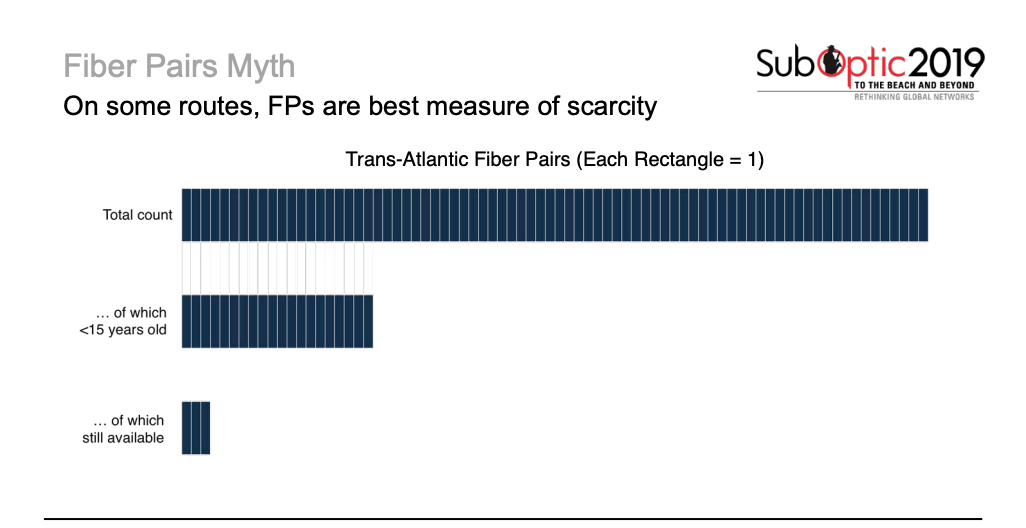

Across the Atlantic, as of early 2019, we have just shy of 80 fiber pairs. Problem is, the largest users of bandwidth—content providers—don’t buy in bits. They want fiber pairs; this is also true of some carriers.

When we weed out fiber pairs on systems 15 years or older, we have a much smaller number of fibers pairs to work with. And many are already purchased. In fact, I could only find three available fiber pairs in the Atlantic, indicating that we’re not in an era of fiber abundance. We’re in an era of fiber scarcity.

Is counting fiber pairs is a useful metric? It seems like it. For certain routes, it might be more useful than traditional methods of measuring supply.

Buying Fiber Pairs

Next, I looked at the likely minimum investment unit (MIU)/primary unit of purchase over time across Atlantic cables. How do we do this?

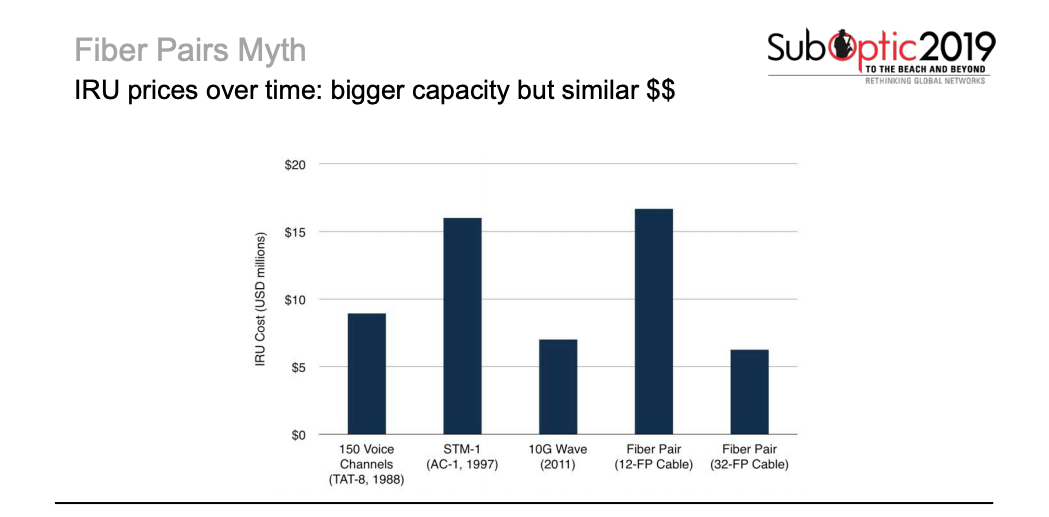

Well, I couldn’t find the exact MIU for TAT-8. But for TAT-10, I know it was 150 voice channels. (That’s old school!) So let’s use that and apply it to the construction costs of TAT-8. When we use that—150 voice channels at a little less than 10 Mbps—we get an IRU of about $9 million.

An STM-1 was reportedly sold for $16 million on AC-1 in 1997. In 2011, a 10G Wave was $6-7 million IRU.

Today, a 12 fiber pair system with an evenly-divided cost is only just above these prices from the last 20 years. And going to a 32 fiber pair system pushes the price below what people have traditionally paid.

What does this mean? It means we might see a new kind of fiber pair buyer in the future.

The Verdict

Even without a huge level of traffic, there is value in holding a fiber pair. It lends an extra layer of control and security. At the (relatively) cheap prices we can envision in the near future, it’s plausible that enterprises, large manufacturing groups, and even governments would consider owning fiber pairs.

On the other side of the coin, a large capacity requirement is still necessary for this arrangement to work. And buying one fiber pair wouldn’t cut it. A buyer would need to purchase multiple pairs for redundancy. And pair that with the current scarcity in the market.

It seems like a proper fiber pair market would be very difficult. But maybe one day we’ll see one. Give it another decade.

It’s not a sure thing, but this fact is officially plausible.

Tim Stronge

Tim Stronge is Chief Research Officer at TeleGeography. His responsibilities span across many of our research practices including network infrastructure, bandwidth demand modeling, cross-border traffic flows, and telecom services pricing.