Would an internet hub by any other name smell as sweet? TeleGeography Principal Analyst Erik Kreifeldt is here to tell us.

While I didn't ask Erik about the naming history of what we know as "internet hubs," I still had a lot of questions: when it comes to hubs—what are we really talking about? What makes a hub a hub? Why are they located where they are? Does the location of hubs influence the cost of internet? And can we say that hubs mark the genuine "location" of the internet?

This is a lot of ground to cover. Erik, as always, broke down my big questions into understandable, bite-sized bits, illuminating what makes a hub a hub.

You can read our interview below or listen here.

Jayne Miller: We talk a lot, both in our research and in content that is shared in our blog or social media, about internet hubs. But I don’t know that we always offer much by way of explanation of what we mean when we talk about internet hubs. So I thought we could start off with you telling us a little bit more about what we mean when we say that, and maybe even a little bit about where those hubs actually are.

Erik Kreifeldt: Sure. In its basic form an internet hub is where internet operators exchange traffic—and there are a few different kinds of operators. There are content network operators that want to get their content onto the internet. And there are internet service providers that want to connect their broadband subscribers to the internet. So those networks want to connect together, and maybe regional internet service providers will connect to global internet service providers who will provide the internet backbone. There’s a wholesale transaction there that will happen at internet hubs.

You’ll tend to find them on a lateral band around the world along the core transoceanic transport routes. And that’s no coincidence they’re located there and we can talk more about that.

There’s a list of criteria and some of it is simply legacy. This is where communications networks have always connected.

JM: When we talk about where they are, the natural thing to ask is “why?” Is there a rhyme or reason? Is it random? As you’ve said, it doesn’t sound random if you look at the map of where these hubs are located.

EK: For sure. There’s a list of criteria and some of it is simply legacy. This is where communications networks have always connected. But they too are connected to certain places for a reason. The proximity to where network architecture is is a big part of it.

You’ll tend to find them on a lateral band around the world along the core transoceanic transport routes. And that’s no coincidence they’re located there.

And the list goes on. You’d like to have a location that’s close to other networks. And just in terms of the facility, you’re going to have a building and the real estate needs to be cost effective. You want that real estate to be actually secure. Secure from natural disasters and from malicious threats. There’s a lot of equipment in there. You want, in addition to being secure, to power all that up. To keep it cool. And you’d like to have cost-effective power. You always want favorable regulatory conditions, and I guess just favorable economic [conditions], to have a location for a truly global internet hub.

Sometimes you might get some of these criteria but not all of them. But those are the kinds of things that if you were doing site selection that you would look for. A lot of these places have already garnered that critical mass and continue to do so because of their legacy and having already achieved these qualities.

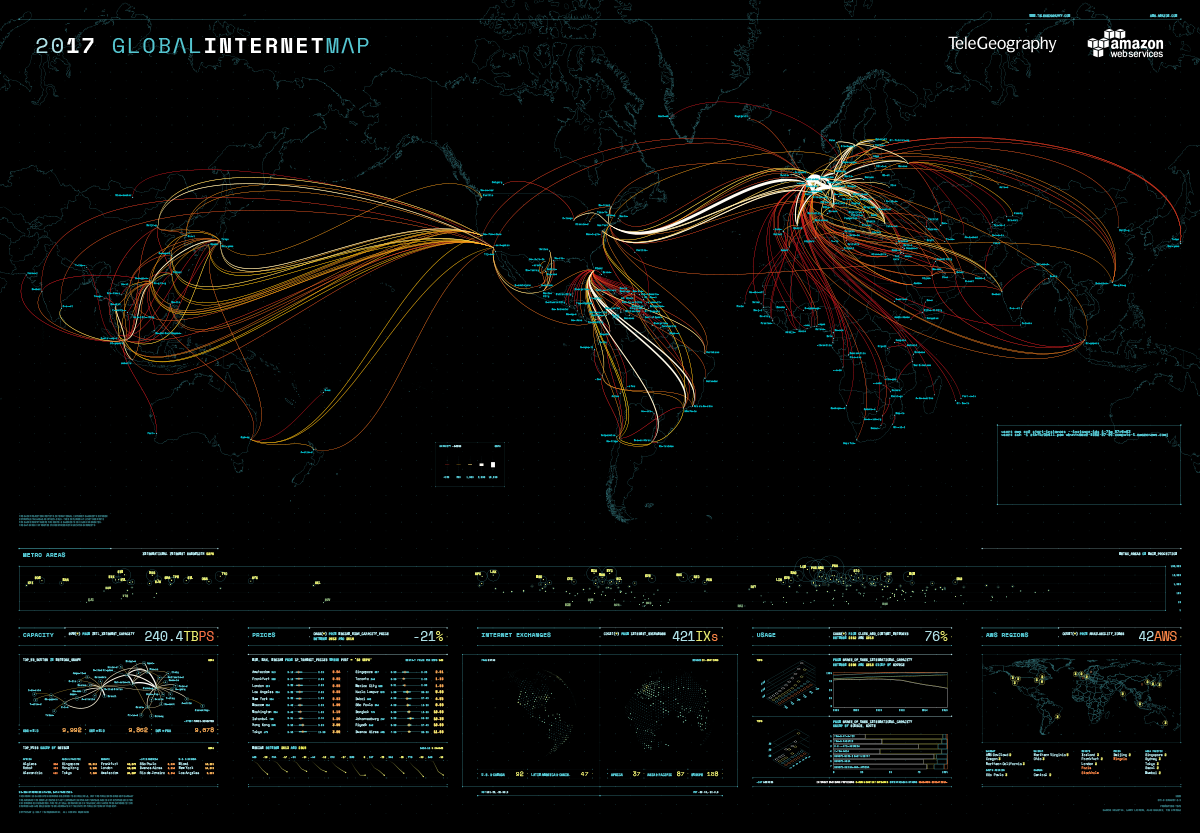

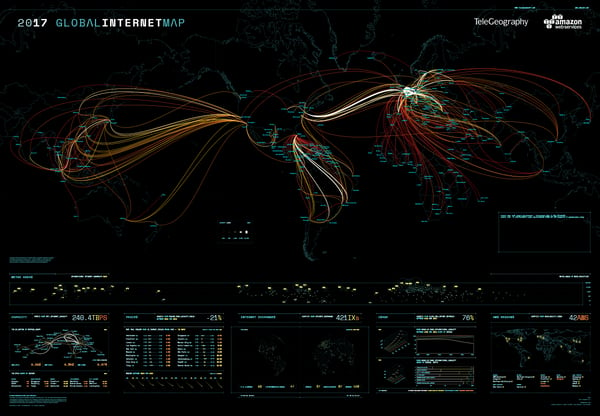

Have a sense of where the hubs are by looking at our global internet map?

JM: So to your point about these qualifications for what makes a site ideal to be a hub—we make a lot of assumptions about the internet being “everywhere.” But this is a misleading assumption.

You and I have talked about places like Latin America. And not even necessarily remote places in Latin America, but where you would “expect the internet to be.” Maybe you’d be willing to talk a little bit more about examples just like that. Where internet access isn’t working the way we think it is working.

EK: Yeah, I suppose there is a kind of assumption that the internet is a nearly ubiquitous mesh of network connectivity. That’s not a completely unreasonable way to think of it because I suppose in most locations you can indeed access the internet. But topologically how that actually happens is more related to what we’ve been talking about—at least in terms of where the connectivity is concentrated.

There are locations where these hubs are, where the activity is concentrated, and I guess there’s another tier of locations that need to get to these hubs. You’re either near them or you’re not. And if you’re not near them in some way for global connectivity, you need to get to them.

As we mentioned earlier, you see this lateral band of hub activity on the global network. If you’re north or south of that you have to connect to it.

There’s a couple of reasons for that. In the most basic sense, those locations don’t really meet the criteria we discussed—that long list of criteria on what constitutes a viable hub. And also just because of legacy of where the internet started and where it persisted for a long time. It really was centered in North America and Europe, and that persists, but that is spreading out. Particularly to Asia.

The big penalty you pay there is the distance. That latency for that traffic to go back and forth. The speed of light is pretty fast, but it does add up when you’re doing a lot of traffic and a lot of computing.

But in some of these other locations, you mentioned Latin America and that’s a great example of the way that network architecture has worked for a long time. Most of the traffic throughout Latin America and South America is actually exchanged in Miami. To put it as simply as possible, the reason for that is it is more cost effective to do it that way than it is to do it more locally or regionally.

You have a certain inertia; once it’s set up that way it can continue to operate that way. And that’s what you see in Latin America. You see that in Africa. The connectivity sort of festoons around the continent—it’s all structured to backhaul that traffic to Europe where all that traffic gets exchanged. And that works. The big penalty you pay there is the distance. That latency for that traffic to go back and forth.

The speed of light is pretty fast, but it does add up when you’re doing a lot of traffic and a lot of computing. So it works. But it’s not ideal, mainly because of the latency and that cost—I mean, you have that big transport cost thrown in there as well.

Carriers have, and content network operators, have addressed this by sort of putting nodes of their content more locally. And that’s good. That works for them. But they would also like to have some more regional hubs of connectivity as well. And indeed, regional network operators will do that.

Again going back to that list of ingredients you need for a truly viable hub, it can be hard to garner that and sustain that in locations where you just don’t have all those attributes. With the concentrated population and network connectivity and just physical geography, too, can work against you. So you have more of this pipe and port type of scenario. From wherever you are, you have the transport back to where the internet “is.” So you get a port into the internet there. And that’s how it works in big swathes of the globe.

Carriers have, and content network operators, have addressed this by putting nodes of their content more locally. And that’s good. That works for them. But they would also like to have some more regional hubs of connectivity as well.

JM: I’m really glad you mentioned both latency and cost.

I’ve used this analogy before; you can tell me if it’s completely off base. But I’ve started to think about the internet in some ways as you would think of a natural resource. It is potentially more advantageous to be closer to hubs than not. Again, there might be the cost consideration. Of course the latency. Am I closer to fast and reliable internet? Is the experience better? Do I pay more for it based on my physical location?

I guess I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about—is that a fair way to think about it? And perhaps more about that cost correlation you had just mentioned because I think that’s an important piece of the puzzle.

EK: Yeah it is. I think it’s a fair analogy. There is definitely a cost component to operating that way. I suppose there is always a balance between having your content concentrated vs. distributed. And there are more and less cost-effective ways to do that.

In this way, there are regions of the world where if you’re near those more mature markets, then you’re going to have an advantage. And if you’re not you’re going to have a disadvantage in terms of cost and performance. Although a lot of that through various means of clever network engineering can close that gap, but you do still have some fundamental cost performance constraints to overcome. Distances, literally.

JM: Well I guess before we let you go and say thank you for telling us more about where the internet actually is: anything interesting in the pricing world that you wanted to share about global internet connectivity that might be of interest to our listeners?

EK: Well it’s interesting how the price for wholesale internet access, which is IP transit, has evolved. Again, in some of these global hubs the prices continue to fall and just when you think it can’t fall any more, it falls some more. The reason it does that is because the costs keep falling as well. There’s a lot of competition out there for that service, so, again, especially in these hubs, we see pretty unrelenting price erosion.

It’s interesting how the price for wholesale internet access, which is IP transit, has evolved. Again, in some of these global hubs the prices continue to fall and just when you think it can’t fall any more, it falls some more.

And in the other scenario—where you have more pipe and port—those prices are falling as well. But the transport portion of that, where transport makes up a greater proportion of the cost or price, might have a different dynamic, but is generally the same trajectory. There’s unit cost efficiencies going on in the transport market as well, which are bringing costs down and competition driving prices down accordingly.

JM: Well thanks, Erik. We appreciate the explainer.

EK: Sure does. My pleasure. Thanks.

Erik Kreifeldt

Principal Analyst Erik Kreifeldt tracks the international network services industry, advising global operators on market trends. With more than 20 years of industry experience—including over a decade of research with TeleGeography—he specializes in strategic decisions that require genuine data, analysis, and insight. Before joining TeleGeography, Erik was an optical networking industry analyst, trade reporter, and optical physics science writer. He continues to draw inspiration from the profound-yet-underappreciated work of maintaining infrastructure essential for global commerce—and awe at how it all gets done.